Understanding the world of biotics

Modern livestock production is facing unprecedented challenges. Overuse and misuse of antibiotics have led to the selection of resistant bacteria, impacting both animal and human health. Economic pressures place strain on both production systems themselves and the efficiency of those systems. Intensive production systems can create biosecurity and welfare challenges while extensive systems can also have adverse health and economic impacts. Improved sustainability and reduced environmental impacts are major considerations for livestock producers, while trying to have as little impact on consumer cost as possible. And cutting through all this is the continual threat of devastating diseases such as Avian influenza, African Swine Fever or Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease that can destroy a production system. It is no surprise that producers look to the diversity of feed additives available to help them manage these challenges.

Feed additives offer solutions

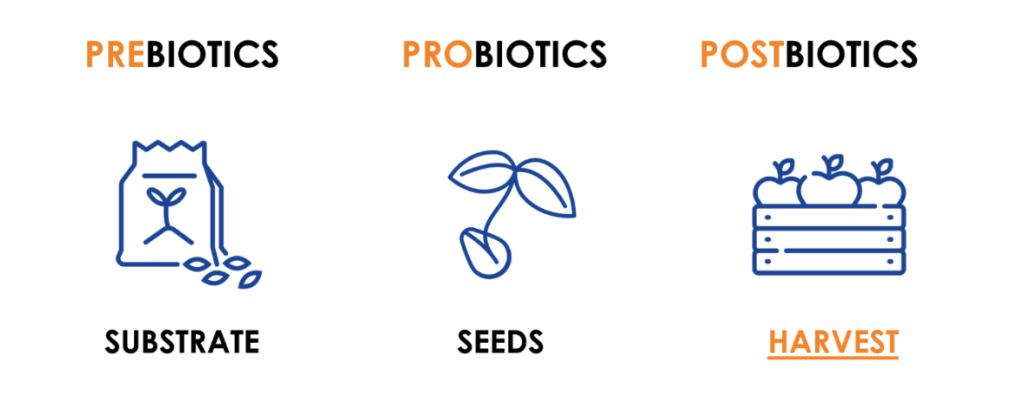

Feed additives can act as growth enhancers, immune modulators, and natural antimicrobials while improving nutrient utilization and efficiency and contributing to reduced environmental footprints. There a numerous categories of additives including the biotics, a catch-all term for arious solutions aimed at supporting and preserving the balance of the diverse microbiotas, but most typically the intestinal tract, to enhance overall health. These solutions generally fall into three primary categories: prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics and can be defined as follows:

A prebiotic is a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit.

Probiotics are defined to be live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate quantities, confer a health benefit to the host.

A postbiotic is a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit to the host.

A good analogy for the biotic categories is growing crops e.g. corn:

We add nutrients (prebiotics) to the soil (subtrate) to help the seeds to germinate and grow. We need the seeds (postbiotics) to grow the corn. We harvest the corn at the end of the crop, when the corn contains all the nutrients (postbiotic) from that growing cycle.

Probiotics versus postbiotics

As mentioned earlier, probiotics are live microorganisms. There are established criteria and quality controls to ensure the probiotic of choice for use in livestock such as 1) correctly identified, 2) fully characterized in vitro and in vivo; 3) safe for use in animals i.e. does not cause disease or harm or could revert to virulence and 4) a minimum number of organisms to elicit an effect. Probiotic organisms can be further selected for other characteristics such as thermostability, adhesion (to intestinal epithelia), acid tolerance and so on.

There are numerous studies discussing the efficacy of different probiotic strains and presentations in livestock, and whilst the data are promising but highly variable, probiotics are not without their challenges. They are live microorganisms, and

therefore susceptible to adverse conditions not conducive to, for example, survival during transport or administration. They also have a limited shelf-life which is highly dependent upon the growth phase when they are prepared. And finally, some

probiotics can take a prolonged period to establish and exert an effect, especially those that are provided as spores via feed to be thermostable; they require time to germinate in the gut and proliferate.

Probiotics are like icebergs!

Irrespective of probiotic performance, probiotics all work in the same fundamental way: they have a physical interaction with the host (via the bacterial cell wall) or other bacteria (competitive exclusion) and they produce various metabolites that interact with other probiotic bacteria, host gut bacteria or host cells themselves to exert an effect. In fact, we can use another analogy, the iceberg. The probiotic organism is the tip of the iceberg, the section that is visible above the water. But underneath the water is a much larger section of the iceberg, hidden from view. This is similar to the vast range of metabolites produced by the probiotic that cannot be seen but are more diverse in characteristics and function.

The advantages of postbiotics

The field of postbiotics arose from this latter characteristic; harvesting those metabolites (and microbial fractions) from postbiotic strains and giving them directly to the target animal. We can potentially provide much higher concentrations of probiotic metabolites in a quicker period than the probiotic can produce in the host. Furthermore, we can change the growing conditions of our probiotic strain to produce more of the metabolites that we wish to focus on. We have the flexibility to adapt our postbiotic composition for a prevailing condition we wish to manage, we can start managing that condition quicker than if we administer a probiotic which needs to proliferate, and we have a solution that is not limited by temperature, other treatments such as antibiotics etc. The fundamental characteristic of postibiotics, as mentioned earlier, is that they do not contain living cells. In summary, postbiotics have several advantages over probiotics:

- Purity

- Ease of preparation

- Production capacity

- Precision of response

- Stable e.g. thermostable, long shelf-life

- Safe; no risk of microbial translocation